Securing Permits: A Bureaucratic Mess & Traveler's Worst Nightmare

Date: 18 May 2007

Location: On the edge of my seat, Berkeley

Tibet. The very nature of the word invokes images of soaring snow-capped peaks, precariously-perched monasteries, and a mystical people concealed for centuries in a mythical Shangri-La. Truth be said, it virtually lived up to this reputation until as late as the 60's, when a spawning China began devouring everything in its path in an effort to lay claim to what had supposedly "always been theirs". While I certainly possess my own strong views on the controversy and resulting detriments surrounding the Red Dragon's invasion of this peaceful Himalayan nation, I'll leave that debate to the protesters. Rather, without trying to become too overwhelmingly passionate about the human rights abuses and freedom movements, I'm going to focus on documenting my upcoming journey to this enchanted, albeit politically turbulent land -

if I can even get in!

Foreign policy - often the bane of every traveler's existence - has truly put me in a predicament this time. Given the territory's contentious nature, gaining access to Tibet has always been an exasperating endeavor, as innumerable permits are required while the region's borders are constantly opening and closing depending on how Beijing feels that day. Timing is absolutely crucial when it comes to planning (more like "attempting") a Tibet trip, with months of anxiety over bureaucratic paper-pushing and crossing your fingers that by the time you do arrive at the border, the Chinese won't be in a bad mood. I can't count how many posts I've come across on the

Lonely Planet Thorntree Forum recounting traveler's horror stories of finally arriving in Lhasa after months of preparation, only to be told to take the next flight out because "Tibet is indefinitely closed".

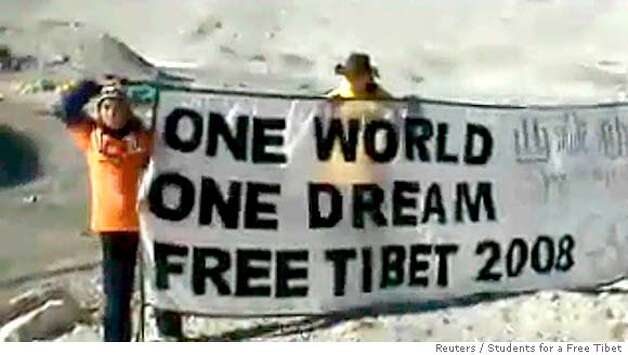

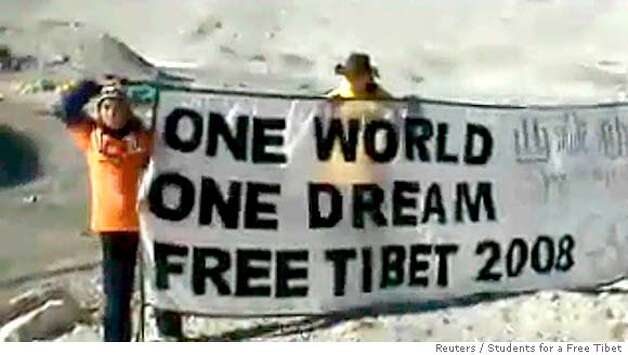

Whether you've heard on the news or not, a group of

Americans recently decided to stage a demonstration on Mt.

Everest in support for Tibetan independence from China. The Chinese government isn't taking this very well and in response to such defiance, all currently issued Tibet permits have been revoked and the region is on total lock-down to foreigners. As we speak, a good number of backpackers are twiddling their thumbs in Chengdu and Golmud (two main departure ports to the region) waiting for some glimmer of hope that the borders will re-open. This is a serious problem on my end because I already have a flight to Lhasa. Translation - I have a very expensive flight to the middle of nowhere

and I can't even leave the airport. What's frustrates me the most is that the system required me to already have purchased a flight to Lhasa in order to file the permit application, even then with no real guarantee that a permit would be granted. And as of today, not only do I not possess the permit, but the region is now completely off limits. And by the way, I'm supposed to leave in a week.

I've been directly conversing with various backpackers currently in China, anxiously awaiting any news of the border situation. Contacting the Chinese consulate in San Francisco and the embassy in Washington have both proved futile. The trip of a lifetime is already falling apart before even starting.

|

| Americans protesting on Everest, a month before my departure |

Updates!

Date: 25 May 2007

Location: Next to the telephone, at my parents' house

I continued trying to get in contact with my agent in LA about obtaining the permits. Every time we inquired about the situation from her, she always replied that she would

get back to us later. That conversation passed about a week ago and I

completely panicked, having now suffered for a month of unknowing where I'm going to end up. We're leaving for China TOMORROW and the fact that we possessed no documentation or plans didn't remotely seem to concern her. The true shocker from today came when the China-based agency told us to go ahead and just "wing it", as in try to get on the Lhasa flight without any permits, papers, or authorization. Something deep down told me that risking a 50/50 chance of breaching the Tibetan border, possibly

to be detained indefinitely by a communist border patrol, just isn't all that it's cracked up to be.

And now, the fist-pump moment we've all been waiting for: I received a call mere minutes ago from our agent saying that the paperwork was approved, the permit was issued, and the border restriction was just lifted - hours before my departure! BAM!

Now that the permit crisis is

somewhat at rest (we can never be too sure what may change in the next several days), I now get to worry

about the other hazard of this trip -

altitude sickness (AMS). I will be going to essentially the highest inhabitable place on earth.

Tibet's capital at Lhasa, one of the lowest regions on the plateau, is already at 12,000 feet. Everest base camp is just around 17,000

feet. Everest itself is at just under 30,000 feet, the altitude most commercial

airlines fly at. AMS works in mysterious ways, as it affects every individual differently regardless of physical fitness or health. Grandma may end up feeling just fine while an Olympic athlete finds himself on his hands and knees, gasping for air. AMS can also prove debilitating and fatal, even if you're strapped to oxygen, with the only remedy being an immediate descent to lower altitudes. Here are the more severe symptoms:

- dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting

- weakness, pins-and-needles, nose-bleeds, swelling of the hands/feet

- Pulmonary Edema (accumulation of fluid in the lungs until you basically drown)

- Cerebral Edema (swelling of the brain until it basically bursts)

Here's to hoping that our rapid ascent will not be marked by any of the above. Thus begins the journey of a lifetime.

Savoring Sights & Sounds in the "City of the Gods"

Date: 29 May 2007

Location: Internet cafe in the Barkhor, Lhasa

After two full days of pure travel, consisting of three flights and a bus trip, we finally entered the fabled Lhasa, "City of the Gods" as the Tibetans staunchly testify. To think that we reached in mere days what takes some Tibetans a year to reach by foot made the entire arrival seem so unmerited, particularly given that Saga Dawa (Buddha's birthday) is approaching and thousands of Tibetans are making the daunting pilgrimage to the sacred city from homes as far as a thousand miles away. Everywhere you turn, Tibetans donning traditional chuba robes and reciting mantras are flooding the city from the countryside to prostrate themselves before the Potala, or former palace of the

Dalai Lama, and the Jokhang, the most sacred temple in the region. As we witnessed along the narrow highway entering the city, true devotees make the grueling journey in the most strikingly penitent fashion, taking a few steps forward before stopping to lie completely flat on their stomachs, legs together and arms outstretched in prayer, only to rise and repeat - for hundreds of miles. This demonstration of religious devotion, or merely the spiritual intensity by which the Tibetans live their daily lives in general, is unlike anything I have ever seen and truly an unfathomable custom to observe. An estimated 50 thousand people will pour into the city by the 31st, with many of them spending the night along the streets and in nomadic camps set up along the city's edge. Meanwhile, all of this mobilization has meant that many army vehicles can be seen strategically placed throughout the city, filled with police in riot gear ready to quell any potential uprising. And when police are not monitoring the streets, you can always wave to one of the hundreds of "eyes in the sky" that keep meticulous watch over the city's inhabitants.

|

| Monks and devotees make their rounds in the sacred old quarter of the Barkhor |

|

| Prayer wheels in a narrow alley |

|

| Detail from one of many ornate temples |

|

| A military presence is everywhere in the city, ready to suppress any political dissent |

Arriving

in Lhasa felt like stepping into a forbidden land. The city is snuggled in the Yarlung Valley, surrounded by "foothills" that are actually far taller than most mountains back in California. The terrain is rocky and dry, textured by ridges and valleys as if the earth were a giant roll of wrinkled fabric. A panorama of golden temple roofs and low, whitewashed buildings sporting staffs of prayer flags gives the entire city a remoteness and richly ancient feeling, even as construction of modern Chinese skyscrapers slowly encroaches. As I already touched upon, the deep adherence to the Buddhist faith not only drives the people, but likewise drives the life of Lhasa itself, as hundreds of Tibetans fastidiously circumambulate the city and its countless shrines. Walking clockwise amidst a sea of devotees, we eventually pushed forward in the long queue to enter the Jokhang and its inner sanctum, where worshipers sat beneath the fierce gaze of a gold and bejeweled Buddha several stories in height. The interior of the temple was dark and haunting, its chambers and narrow corridors lit solely by the flickering of yak butter candles whose pungent aroma clashed with the scent of spicy sandalwood and earthy juniper incense. With the murmuring chant of monks echoing off of brightly painted walls depicting radiant gods and fiery demons, the entire experience was as eerie as it was ethereal, a complete overwhelming of the senses.

|

| Worshiping at the Jokhang |

|

| Giant incense burners filled with dried juniper fill the old city with an earthy fragrance |

|

| Yak butter candles at one of the altars |

|

| Larger than life gold idols in the sanctuary |

|

| Vivid temple murals of mighty gods and ferocious demons cover every wall |

A similar feeling was felt at the Potala, the fortress-like palace of the Dalai Lamas that quintessentially defines the Lhasa skyline. It sits proudly upon a natural hill in the center of the city, and can be seen from every direction as the spiritual, artistic, and engineering jewel of Tibetan culture. Home to the spiritual leaders of Tibet from the 17th to the early 20th century, it boasts a staggering 1000 rooms and 10 thousand shrines over thirteen stories worth of construction. Since the exile of the 14th Dalai Lama to India in 1959, the palace has served solely as a museum, even though Tibetans still bow before it when passing in the street. Its great halls

house thousands of statues of enormous proportions, all covered in gold, silks, and

semi precious stones. A monk in one of the chapels witnessed my admiration and bestowed upon me the truly honorable gift of a khatta, or traditional white silk scarf, that he ceremoniously rubbed on the gold tomb of the 8th Dalai Lama. I bowed to him with hands in prayer as he draped the blessed fabric over my neck, feeling metaphysically moved as well as giddy with the thought of having physically acted out a scene from "

7 Years in Tibet". This country may be a wild wasteland to many people, but

it certainly does not lack in cultural and spiritual wealth.

|

| The Potala Palace, the iconic landmark of Tibet |

|

| Devoted workers renovate the inner grounds, stomping the mud floor while singing traditional songs |

|

| Pilgrims prostrate themselves on the street when passing before the Potala Palace |

Today we enjoyed a traditional lunch of grilled yak meat (exceptionally tough), mutton, and hand-pulled noodles, an archetypal meal for the semi-nomadic populace on the plateau. We are currently at an altitude of roughly 12,000 feet, experiencing a level of ultraviolet radiation that gives even my father a decent sun burn. Hours after landing, we already began to experience the basic symptoms of altitude sickness, my mother dealing primarily with headaches and dizziness, while my father and I faced bizarre tingling in the face and fingers with an occasional nosebleed (more likely due to the arid climate). At one point last night, I awoke feeling a little out of breath. It was

actually quite shocking and scary at first, as none of us have ever felt physically threatened on a trip simply by the nature of our geography. Nevertheless, we've been acclimating before our long anticipated family road trip - to Everest.

.JPG) |

| A slab of grilled yak meat (more like yak jerky) |

|

| Gold and silk ritual parasols decorate a temple roof at the Drepung Monastery outside Lhasa |

|

| Young monks return to their quarters after a morning of meditation and chanting |

The Journey to Mt. Everest: A Tale of Insight & Intrigue

Date: 6 June 2007

Location: Internet cafe in the Barkhor, Lhasa

300 miles of rough road-tripping.

Towering mountains, lowland valleys.

Scorching sands, freezing snow.

Golden temples, mud-brick houses

Yaks, horses, goats, vultures.

Despite my family having traveled every

year since I was conceived, all too frequently to what many envision to be the literal “ends of the earth”, the road trip to Mt. Everest was completely unlike any journey we’d ever

experienced prior. It only took a mere six

days to live a lifetime, to feel every possible emotion in the spectrum, to suffer from almost

every kind of ailment, and yet most amazingly, to witness every possible extremity

this planet has to offer in one setting. It would take me far more than the hour I've spent at this internet cafe to fully convey the totality of the adventure felt on this deeply personal

expedition. Momentarily speechless, even my pictures can only express 999 words of the thousands more worth writing to describe a place as vast as Tibet

– the Roof of the World.

After stocking up on supplies and confirming with our guide that the 4x4 was fueled and functional, we embarked on a first day that had already proven to be an adventure in itself. We sped off in our Land

Cruiser from the capital at Lhasa

(elevation 12,000’) through the dramatic Yarlung

Valley in southern Tibet,

passing spectacular scenes of traditional agrarian life. From colossal carvings of the

Buddha on cliff walls to snaking rivers naturally carving their own way through the

valley floor, we began the steep ascent up and over the Kambala pass (16,300') to view Yamdroktso

Lake (14,500’), a dazzling sea of

azure blue amidst a greater beige ocean of rock. Since the beginning of the trip, the entire plan seemed simple and relaxed,

having a teenage Tibetan guide and middle-aged driver deliver us to some of the most elusive and visually dramatic locations of exquisite natural beauty the earth has ever

produced. However, as the trip progressed, we began to realize that, as every facet of life in

Tibet has experienced under Chinese occupation, it would neither be that easy nor emotionally settling. With Tibet as the hub of such great sociopolitical controversy since China’s

cultural revolution, the Chinese authorities have not failed in making

traveling within the region exceptionally complicated. Foreigners are forbidden from traveling anywhere without a state-approved guide. Thankfully, both our guide and driver happened to be actual Tibetans, as opposed to Chinese, giving us the benefit of a more legitimate experience and service. On the open road, away from eavesdropping agents and video surveillance, we were told the societal plight of the Tibetan people as well as the human rights atrocities designed to keep them suppressed as second-class citizens in their own land. In addition to requiring government authorization to simply enter the province, a police-issued permit is

mandatory for every site of interest outside of Lhasa, to be inspected at checkpoints in every town. It had already taken weeks prior to the trip, a good amount of money, and plenty of

stress to guarantee us permits for travel within Tibet, a process made even more problematic following

the recent American protests for Tibetan independence a month earlier.

|

| Our driver, a middle-aged man from Amdo, drives hundreds of miles to support his wife and two daughters |

|

| Back before cars reached Tibet, people rode yaks. Taken above Yamdroktso Lake. |

Unfortunately, we did not realize just how difficult it would get until we

arrived in Shigatse

(12,800’), where we found ourselves overwhelmed by some sort of shady,

underground transaction entirely for the purpose of obtaining a single permit

that we apparently lacked. We were told that we could not proceed any further without this document, although after a lengthy, restless discussion between our driver and guide in Tibetan, a solution was supposedly plausible. Cruising dubiously through town, we found ourselves parked at what seemed to be someone's vacant residence, being told to remain in the vehicle. Fifteen minutes later, our guide returned, closely clutching an envelope with

photocopies of our passports and other documents. We were then taken to the center of town where a bustling children's festival was taking place, tents filled with families eating and playing traditional gambling games in a crowded carnival-like atmosphere. Again, we were told to wait in the vehicle. Everything was done with considerable suspicion of people potentially watching, our guide informing us that obtaining the missing permit was indeed possible but would require us to leave our passports and a cash payoff of a couple hundred yuan with a man they simply referred to as “the leader”. Our hearts sank having been thrown into such a clandestine predicament that would either push our trip forward or stop it dead in its tracks. After considerable debate, we ultimately took the risk, as our guide quickly vanished into the crowd with our money and documentation. After half an hour, he eventually re-emerged and explained that it was necessary to skip town for a day, reassuring us that our passports and permits would be returned in due time. As we set off down the road, with the town of Shigatse gradually disappearing on the horizon, we could not help but feel unbearable anxiety in realizing

that we had just left our only forms of identification with a faceless character

in a sea of tents 90 kilometers away.

|

| At a children's festival, the setting for some super shady, covert transactions |

Trying not to think about what would become of our crucial documents, we enjoyed the outpost town of Gyangze

(13,000’) and its rustic streets, along with the imposing 14th-century Palkhor monastery. Like a

scene from a rugged western frontier, the town possessed an air of remote romance, dusty and orange in the shadow cast by an ancient fortress crowning a dry cliff top in the setting sun. As our guide led us through the monastery’s dark sanctuary, a heavy aroma of incense and yak butter filled a breathtaking

chamber inhabited by a number of gold and jeweled deities, their gilded faces glistening in the flickering candle light. The monks sat in near darkness, chanting deeply alongside the light tinkling of bells and raucous thuds of temple drums in an ambiance that propagated the omnipresent spiritual vibe Tibet is renowned for. To describe the scene as "meditative" would be an injustice to the mystical energy and mental focus mastered by these red-robed teachers. As for my mother, the passports were the only things on her mind that entire day. We returned to the ongoing festival in Shigatse the next morning with our fingers crossed, ultimately to find our passports returned along with the required permits. We never met

“the leader.”

|

| Overlooking the ruggedly romantic town of Gyangze and its formidable fortress |

|

| The 14th century Palkhor Monastery and Stupa |

|

| Monks deep in chants within the inner chapel |

Continuing on up to the great Tashilhunpo monastery cradled by jagged cliffs, we

stood in the presence of a gold-plated bronze Buddha 86 feet in height, supposedly dubbed the largest bronze statue in the world. Given that a single finger of this silent giant was as tall as me, I came to realize that virtually everything here in Tibet

must be measured on a colossal scale. And that scale became even more incomprehensible as we gradually bounced our way further south toward the heart of the Himalayas. Apart from an incident where our driver nearly got us into a fatal head-on

collision after falling asleep, in which my father had to grab the wheel to evade a fully-loaded semi, the journey to Everest was exceptionally pleasant

and thoroughly awe-inspiring. Up through rocky mountain passes, down through cavernous

gorges, through dry heat and wet cold, we passed countless villages comfortably perched at

around 16,000 feet in altitude. However, with such extremes came the

unavoidable (and potentially fatal) nuisance that is altitude sickness. Apart from a brief breathing issue at

night reminiscent of a small asthma attack, I was relatively fine. My father faced incessant

nosebleeds and numbness throughout his body, but was otherwise decent. My mother, however, experienced the worst symptoms as she struggled with excruciating migraines and nausea, all while trying to

fight a severe head cold and swollen glands. It was another gamble, as we knew that should her condition worsen, there would be no way for us to return to Lhasa as quick as necessary. We spent

a night in Shegar, a cold and desolate village that we'd later learn

becomes overrun by hundreds of vicious wild dogs, growling and fighting all throughout the night making it impossible to sleep. But while our nights tested our endurance and patience, it was the beauty of

the journey and interacting with locals during the daytime that made it all worthwhile. We were

fortunate to witness a rare and fascinating event of true Tibetan culture, a circle

dance performed by villagers on the side of the mountain pass. Invited to drink barley

beer with the elders, we were fully entertained by a swarm of smiling children, some of

them eager to see Westerners for the very first time. Elaborately decked in heavy woolen robes, tribal necklaces of turquoise beads with coral, and

gaudy silver ornaments, the genuine geniality of these isolated villagers will never be forgotten.

|

| We passed many remote villages in the Himalayan foothills |

|

| Herds of yaks cross the road |

|

| Poor Tibetans beg along the road |

|

| The winding dirt road leading south towards Everest |

|

| We were invited to join a village festival |

|

| Villagers performing a circle dance in traditional attire |

|

| A young girl is captivated by our presence |

|

| An old woman who offered us barley beer |

|

| A village girl points to her teeth in curiosity after seeing my orthodontic braces, mistaking them for "mouth jewelry" |

|

| Rural Tibetans are exceedingly friendly and often highly comical |

|

| The mighty Himalayan range, seen from 60 miles away |

After four straight days of criss-crossing vast terrain, interacting with weather-beaten

nomads, and holding our breaths at plenty of police checkpoints, we arrived at Everest

base camp, which was nestled

at a staggering altitude of around 17,000 feet. The scene was exquisitely savage and as enthralling as I imagined it to be. A tiny strip of goat-hair tents managed by different Tibetan families lined the main path leading towards the foot of the mountain, each ready to receive what few visitors may happen to pass through. Out behind the dirt path was a communal pit latrine, where men and woman could squat side-by-side in the open over holes in a rickety set of planks. A leg of raw goat meat hung off of a hand-painted sign, the need for refrigeration rendered void given the summertime chill. We settled down with two Tibetan teenagers who

demonstrated gracious hospitality through their provisions and making us feel completely at home

despite the unforgiving environment that surrounded us. As night fell, below-freezing temperatures enveloped the camp while we remained snug in our tent, bundled tightly in ballooning layers of woven blankets around a small oven fueled by dried yak dung. While being

mothered by a girl younger than me, we all could not help but feel the looming

presence of the “Universal Mother,” an appropriate title the Tibetans give to the highest mountain

in the world. Everest was simply mind-blowing. At 29,029 feet, its blinding white face burst from the rock-strewn floor as the most intimidating work of

nature I’ve ever come across. Despite formidable gusts of wind and temperamental cloud cover on our first day at base camp, our image of

Everest could not have been more perfect as we received an exceptional and

completely unobstructed view the next day. Given such fortune, we were also lucky to have been present at the same time

that an Australian expedition was planning to summit the mountain, observing their oxygen tanks and climbing equipment piled high around their tents in the "permit-only" section of the basecamp. But Everest was just as humbling as it was exciting. Feeling exceptionally diminutive and entirely overcome with piety, I kept with Tibetan Buddhist tradition by tying down my own personal set of

prayer flags at the base of the mountain. Inscribed with the signatures, wishes,

and prayers of my family, friends, and teachers, I could not help but feel an immense sensation of satisfaction in knowing that I could somehow share this sacred experience with everyone dearest to me, if not in the flesh then at least in spirit.

|

| Base camp at Mt. Everest. This part of the camp is reserved for authorized climbers only |

|

| Close-up of the North Face of Everest during the day |

|

| Australian expedition tents |

|

| Supply tents with plenty of oxygen tanks |

|

| Hanging personally-signed prayer flags on the shrine at the base |

|

| The section of base camp reserved for non-climbers wishing to spend the night |

|

| A girl lights a dung-fueled stove in our tent to keep out the below-freezing temperatures |

|

| A leg of raw goat meat waiting to be cooked |

|

| Everest, as seen from Rombuk Monastery |

The Sacred Lake of Namsto: A Photo Gallery

I've included for your enjoyment a few selected photos taken from a visit to the area around the sacred lake of Namtso (15,479'), on the road trip back from Everest.

|

| Herding yaks on the Tibetan Plateau |

|

| The tent of a nomad family on the plain surrounding the lake |

|

| A nomad mother and her four daughters |

|

| Invited into the tent of one nomad family |

|

| A scene from the Wild West of the East. Taken at a tent village on the shores of Namtso |

|

| Dawn over shrines on the lake, a woman carries a water jug on her back |

|

| Snow deposited overnight on the surrounding mountains |

|

| A tent shop sells snacks and oxygen |

.JPG)